Boise State University apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation US.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

As Americans anticipate summer vacation, many are planning trips to our nation’s iconic national parks, such as the Grand Canyon, Zion, Acadia and Olympic. But they may not realize that these and other parks exist because presidents used their power under the Antiquities Act, enacted on June 8, 1906, to protect those places from exploitation and development.

The Antiquities Act has saved many special places, but at times its use has angered nearby communities. Some critics argue that presidents have used the act to restrict natural resource development. Others simply do not like the fact that the president has such power – even though Congress gave it to presidents by passing the law.

As a seasonal park ranger at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area in the 1970s, I hiked through areas that were first protected under the Antiquities Act. They include Zion and Capitol Reef national parks, Natural Bridges National Monument and the area that would become the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Much of the scenic redrock Colorado Plateau region, which covers 140,000 square miles in the Four Corners region of the Southwest, has been protected from development under the Antiquities Act.

While the Antiquities Act has played a crucial role in the growth of our national park system, it has become a flashpoint for disputes from Alaska to Maine over protection and use of public lands. For that reason, it works best when it is not used arbitrarily or too often, and when the public understands and supports its use.

The Antiquities Act was passed to conserve the stunning archaeological treasures of the American Southwest. As settlers, prospectors, ranchers and explorers pushed into the region in the late 1800s, they discovered unique and spectacular sites left by Anasazi – ancestral Pueblo people who lived in the area from about A.D. 700 to 1600. Examples included dwellings such as the Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House at what would eventually become Mesa Verde National Park.

These discoveries led to pot hunting, looting and shipping of artifacts to institutions in the east and abroad. Scholars began to call for controls. J. Walter Fewkes, a prominent archaeologist, warned in 1896 that unless this plundering of ancient sites was curbed, “many of the most interesting monuments of the prehistoric peoples of our Southwest will be little more than mounds of debris at the bases of the cliffs.”

Congress passed the “Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities” on June 8, 1906. Its key provision states:

[T]he President of the United States is hereby authorized, in his discretion, to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments, and may reserve as a part thereof parcels of land, the limits of which in all cases shall be confined to the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.

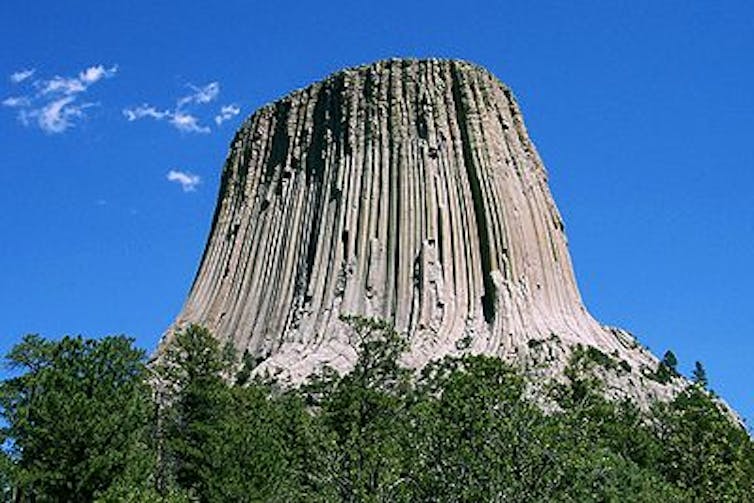

How fortuitous it was for the national park system that Theodore Roosevelt – who strongly believed in using his authority to conserve precious natural resources – was president in 1906. Over the next three years Roosevelt designated 18 national monuments, some of which Congress later elevated into national parks or national historical parks. They include Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, a landscape of fossilized trees and a “painted desert”; Chaco Culture National Historic Park, a stunning and complex Anasazi site in New Mexico; and Pinnacles National Park, a swath of rock spires and woodlands in California’s Central Coast Range.

Every U.S. president in the past century except for Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon and George H.W. Bush has used his authority under the Antiquities Act to create new national monuments. Both Congress and the president can take this step, but in practice most monuments have been designated by presidents. (In contrast, only Congress can designate national parks.)

Both national monuments and national parks can be large in size. The original Grand Canyon National Monument, proclaimed by Theodore Roosevelt in 1909, covered more than 800,000 acres. Although the law explicitly says that monuments should be as small as possible consistent with conservation, courts have upheld the creation of large monuments if the proclamations justify protecting large areas.

Use of the Antiquities Act has fueled tensions between the federal government and states over land control – and not just in the Southwest region that the law was originally intended to protect. Communities have opposed creating new monuments for fear of losing revenues from livestock grazing, energy development, or other activities, although such uses have been allowed to continue at many national monuments.

In the 1930s Wyoming residents objected when John D. Rockefeller offered to donate land that he owned near Jackson Hole to enlarge the original Grand Teton National Park. When Rockefeller threatened to sell the property instead, President Franklin Roosevelt combined the land with 179,000 acres from Grand Teton National Forest to create a national monument in 1943, which later was added to the national park. Wyoming Republican Senator Edward Robertson called the step a “foul, sneaking Pearl Harbor blow.” In 1950 Congress amended the Antiquities Act to require congressional approval for any future monuments designated in Wyoming.

The next controversy flared in 1978 when President Jimmy Carter, acting on advice from Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus, designated 17 national monuments in Alaska totaling more than 50 million acres. Carter took this step after one of Alaska’s senators, Mike Gravel, delayed action and threatened to filibuster pending legislation to create national parks, national forests and wildlife refuges on these lands.

Alaskans protested, but in 1980 Congress passed compromise legislation that converted the lands to parks and refuges. Once again, Congress amended the Antiquities Act to require congressional approval for any future national monuments larger than 5,000 acres in Alaska.

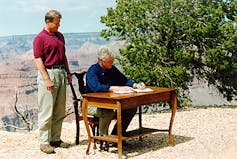

In 1996 President Bill Clinton designated the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah, a spectacular swath of redrock canyons and mesas in the Colorado Plateau. Clinton administration officials sought to protect the areas from proposed coal mining nearby. The Interior Department tried to soften local opposition by offering Utah access to coal resources elsewhere through land exchanges. But Clinton proclaimed the monument without much advance consultation with local communities, leaving some Utahans feeling blindsided and resentful years later.

The Antiquities Act is still a valuable tool. President Obama has used it to protect several million acres in Nevada, Texas and California. But future designations will succeed only if federal agencies consult widely in advance with local communities and politicians to confirm that support exists.

Invoking the Antiquities Act inevitably raises broader conflicts over preservation versus use of land and state versus federal land management. These issues are deeply rooted in Western states, and have flared up in recent years, most recently in the standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.

Sometimes these debates produce compromises. In Idaho, pressure from conservationists to create a national monument in the Boulder White Clouds Mountains spurred passage of a bill last year that created several wilderness areas there. No new roads will be built in these zones, but existing grazing and most recreation activities will continue.

A similar controversy is generating heated debate in Utah, where conservationists and tribes are lobbying for the federal government to designate a scenic area called Bears Ears as a national monument. The region is sacred to Native Americans and contains thousands of archaeological sites, many of which have been looted and vandalized.

In Maine, businesswoman Roxanne Quimby has tried for more than a decade to donate land she owns to the federal government to create a new national park and recreation area. Opponents say this step would harm the timber industry and force federal authority on a region that prizes local control. Now the family is proposing to have the land designated as a national monument. Environmental advocates openly call this action a first step toward creating a new national park.

Another use of the Antiquities Act bears watching: using it to conserve and spotlight sites that mark important moments in American history, such as the new Cesar Chavez National Monument in California. Perhaps using the act to celebrate our history and learn from our failures can increase support for it as an enabling instrument of American conservation.